Lab 0: Haskell Install Party and Git Intro

Today’s Goals

- Install needed software.

- Practice submission via git.

You will submit a simple file proving you have these things working (explained below).

As with all lab assignments, this small submission is technically due Thursday by 10:59 PM. However, unlike most assignments, you should be able to finish before class ends today.

You may use the lab computers or your own computer to turn in assignments.

If your CNetID includes uppercase letters, to log in to the lab machines you may need to type your username in all lowercase.

Install

To create and turn in your assignments, you want four things on your computer:

- A terminal — to compile and run your code

- Haskell — of course

- A good text editor — to write your code

- Git — to turn in assignments

Quick Links

- Haskell: Download Haskell Platform Core

- Text Editor: Atom or Visual Studio Code or Sublime Text or Vim or Emacs (Vim and Emacs are often preinstalled, check on your command line).

- Git: Download Git, includes a terminal for Windows (“Git Bash”).

A Terminal

Compiling and running Haskell programs generally happens on the command line, so you’ll need to have a terminal application.

All macOS machines come with an app called “Terminal” installed.

On Windows, if you don’t have a terminal you’ll get one for free when you install git below (it will be called “Git Bash”).

Terminal Basics

You will want to develop some comfort on the command line. There is a primer workshop in CSIL coming up that I recommend you attend if you haven’t worked with the command line. Here’s the bare essentials:

See where you are (“print working directory”):

$ pwdNote the $ above is just an indication that you’re on a command line. All you have to type is pwd.

List what’s in this folder:

$ lsList all files (files that begin with . are usually hidden), with “long” information:

$ ls -alLearn about any command by looking at its man page (manual page):

$ man ls(Hit q to quit.)

Enter a folder (“Change directory”):

$ cd some_folderGo up one folder:

$ cd ..The “root” folder is /, and your home directory is ~.

Make a folder:

$ mkdir new_directoryMove (or rename!) a file or folder:

$ mv old_name new_nameCopy:

$ cp old_file new_fileCopy a folder (“recursive” copy):

$ cp -r old_folder new_folderLog on to a remote machine:

$ ssh username@computername.cs.uchicago.eduEach computer’s name is written on the side of the machine. Or, there are a few machines for shared use. You can leave SSH with ctrl-d.

Copy a file to another machine:

$ scp some_file username@computername.cs.uchicago.edu:~/some/path/on/other/machineIf you use a terminal text editor like emacs or vim, you can use ssh to do your homework remotely.

If some app is running in a terminal and you want it to stop, hit ctrl-c. If some app in the terminal is asking you for input and you don’t want to give it any, hit ctrl-d (end of input). ctrl-d is also a way to end your terminal session.

Haskell

The lab computers should have Haskell pre-installed. On your own machine, you can install Haskell Platform. Despite what the lecture notes may say, the core install should be fine.

To see if you have Haskell installed correctly, open up a Terminal and run:

$ ghciMac users may need to install the XCode command line tools, which can be done most efficiently with:

$ xcode-select --installOn Windows, if you are using Git Bash, you may need to tell it where to find Haskell:

$ echo 'PATH="C/Program Files/Haskell Platform/8.2.1/bin/:$PATH"' >> ~/.bashrcRestart Git Bash and try running ghci again.

When GHCi opens, try some basic commands:

Prelude> 2 + 2

4

Prelude> 8 ^ 10

1073741824Usually on a terminal you stop a program by typing ctrl-c, but in GHCi ctrl-c will only stop a long-running line of code. Instead, you leave GHCi by typing ctrl-d, which means “End of Input”.

A Good Text Editor

Microsoft Word ain’t gonna cut it. You want a text editor that makes your code colorful and automatically indents every new line you type.

Two popular free GUI text editors are Atom and Visual Studio Code. The lab machines have Sublime Text installed; you can try it for free on your own machine and if you like it then it is a tool worth purchasing. If you use Atom, at least install the language-haskell package from within Atom. Similarly for VS Code: install at least the Haskell Syntax Highlighting extension from inside VS Code.

On the command line, the popular options are vim and emacs. Both these editors are pre-installed on the lab computers. Using a command-line editor takes some practice, but an experienced user can learn to rapidly perform complicated edits. Another advantage is that these editors can be used on remote machines over SSH. The main disadvantage is you can’t use your mouse.

Git

Git (pronounced like “get”) is a version control system. Git lets you take snapshots of an entire folder and stores the snapshots as “commits”. With git you can:

- Keep a history of changes to your project.

- Work on your project on different computers.

- Work on different versions of your project.

- Share your project with collaborators.

- Quickly incorporate changes from collaborators.

To use technical terms, Git is a distributed version control system. Because of its speed and flexibility, it has become the leading tool for managing source code. For example, Github is the world’s largest storehouse of open source projects. However, Github did not make Git—that honor goes to Linus Torvalds, who you may recognize as the creator of Linux.

If you’re looking for a version control system to learn in 2017, Git is the one. You won’t be using many of its features (for example, you won’t be collaborating with each other), but you will use Git to submit code and that will give you a taste of what you can do.

You can download git here. Mac OS X computers may already have git installed.

Verify Git Installation

To check if you have git installed, run this command on the command line:

$ which gitYou should see a path, like:

/usr/local/bin/gitIf you do, you’re good to set up git.

A Bit Of Git Setup

Check your Git config and see if you have a name and email set.

$ git config --listIf you don’t have a name and email set, choose the name and email that will appear on all your commits. You do not have to use your UChicago email.

$ git config --global user.name "Name"

$ git config --global user.email "email@example.com"Enable color to be happier:

$ git config --global color.ui autoGetting Your Repository

We created git repositories for all of you. You need to gain access to yours.

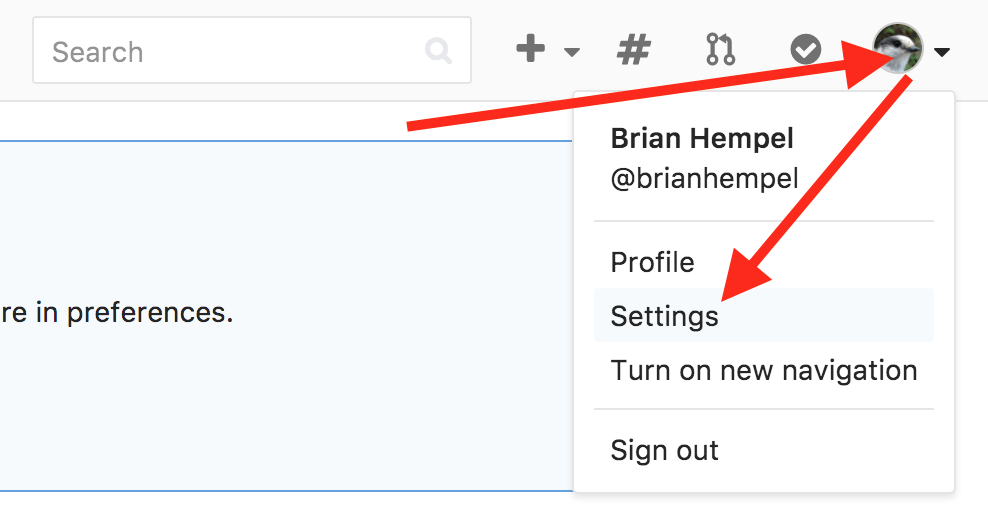

Log in to https://mit.cs.uchicago.edu/. This is a web interface where you can view your repository.

Find the settings.

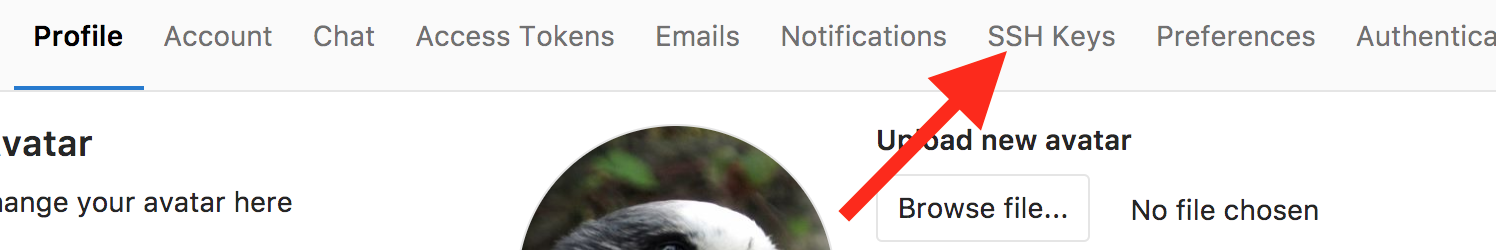

- Go to manage your SSH Keys.

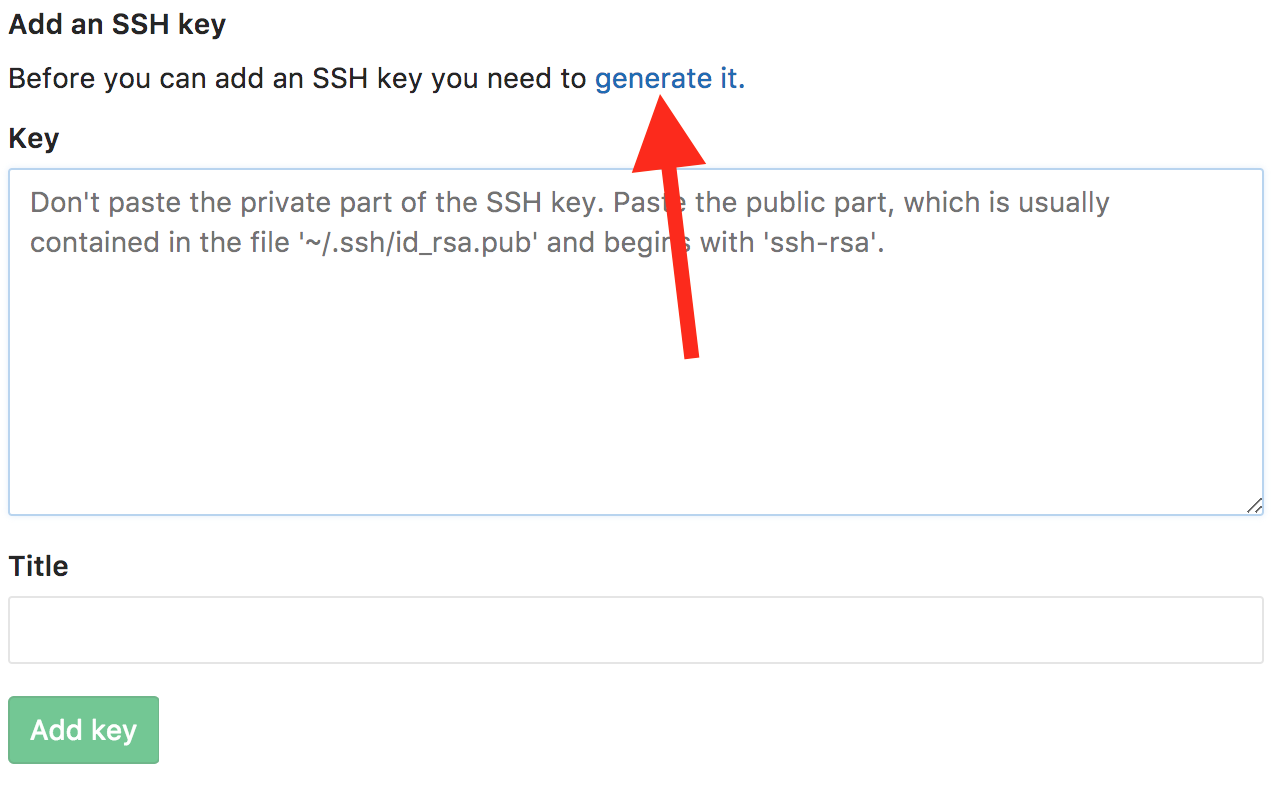

- If you don’t have an SSH key (usually they are stored in the

~/.ssh/folder), follow the directions for generating one (I always skip the password step).

Public key encryption is one of the coolest things in computer science. Unfortunately, we don’t have time to discuss it. Just make sure you give Gitlab your public key not your private one.

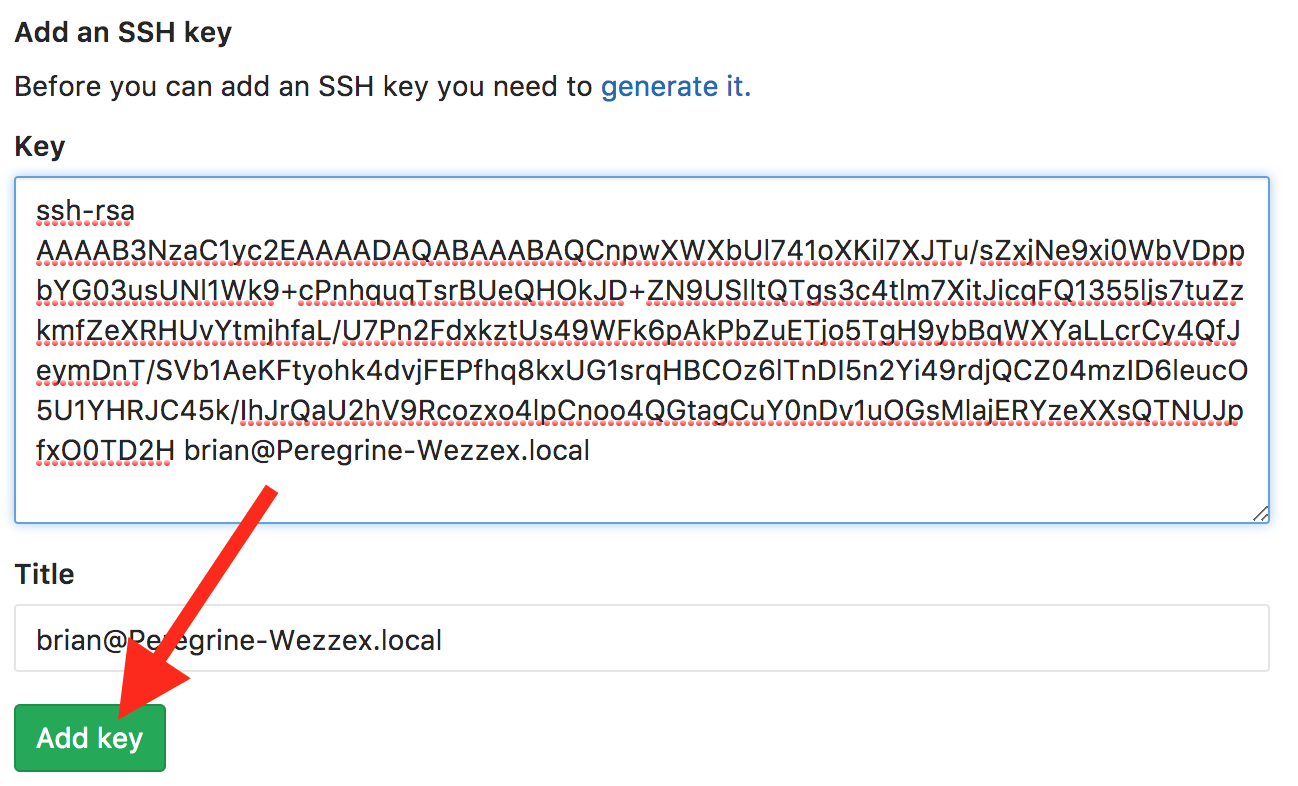

- Copy/paste your public key into Gitlab.

There. Now, when you try to talk to the submission system from your computer, the submission system knows it’s your computer and not someone else. Let’s give it a go.

On the command line, navigate to your folder for this class. Now, clone the repository from the submission system onto your computer:

$ git clone git@mit.cs.uchicago.edu:cmsc16100-aut-17/yourcnetid.git

$ cd yourcnetidNote: Some Mac users have reported trouble if they try to clone into an iCloud directory. Clone outside of iCloud.

You will asked about trusting a computer: say yes this first time.

Each of your labs will eventually be its own folder in this one big repository (e.g. folders named lab0, lab1, lab2, etc.). Well, it’s not a big repository yet. But it’s your one repository for this term.

Note: This is your lab repository. You can store your homework in it if you like—it will be ignored. But complete the labs in the lab0, lab1, lab2, etc. folders that will be provided and do not change their locations within the repository.

This Week’s Submission

Let’s make sure Haskell is working and practice Git’s workflow.

There should be a lab0 folder in your repository. Using your text editor (not the mit.cs.uchicago.edu web interface), make a new file in the lab0 folder called Hello.hs. Paste in this program…

data Level

= Undergraduate

| Masters

| PhD

| Other

deriving Show

name :: String

name = "Your Name Here"

level :: Level

level = Undergraduate

major :: String

major = "Your Major or Program Here"

why :: String

why = "A sentence about what inspired you to go into CS or why you are taking this class or what you hope to gain from this course."

distance :: Int -> Int -> Int

distance rate time = rate * time…and put in your own answers for name, level, major, and why.

Make sure to save the file as Hello.hs in the lab0 folder.

On the command line, make sure you are in the lab0 folder and then start GHCi by typing:

$ ghciYou should see Prelude>. To load the file, use :l (the letter l)

Prelude> :l HelloYou should see:

Prelude> :l Hello

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( Hello.hs, interpreted )

Ok, 1 module loaded.

*Main>You can now use the items you defined.

*Main> name

"Chuck Norris"

*Main> level

Other

*Main> distance 15 20

300Let’s turn in this file. There’s a still another modification we’ll make below, but it’s a good idea to submit your changes as you work.

Exit GHCi by hitting ctrl-d. Then run:

$ git statusYou should see something like:

On branch master

Starter code for lab0

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

Hello.hs

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)Git is telling you that it’s not watching the Hello.hs file. Any changes to this file will be ignored.

Tell Git to track your file with git add.

$ git add Hello.hsNow if you run git status you should see:

On branch master

Initial commit

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: Hello.hsWe haven’t actually created a snapshot (a commit). We’re just telling Git what files we want to include in the commit. If we had more files, we could also add them to create a single big snapshot with multiple files.

Let’s just make a commit with this file.

$ git commit -m "Hello.hs with some personal info"The string after -m is your message for the commit. It’s sort of a name for the snapshot. Use it to describe what you changed since the last commit.

You can see a log of commits with git log:

$ git log

commit 30a672d7a3b3f615080a7fd79eccaa831f5285dc

Author: Brian Hempel <brianhempel@uchicago.edu>

Date: Mon Oct 31 22:46:35 2016 -0500

Hello.hs with some personal infoThe commit is still only on your own computer. To push this change to the remote repository (the mit.cs.uchicago.edu server that’s acting as our submission system), just type:

$ git push(For your very first push, you may have to type git push -u origin master.)

You should see a message about pushing to master.

Okay, now it’s time to make a real change. Open Hello.hs and paste this code at the bottom:

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn "Hello, world!"

putStrLn ""

putStrLn ("My name is " ++ name ++ ".")

putStrLn ("I am a " ++ show level ++ " student.")

putStrLn ("I'm going into " ++ major ++ ".")

putStrLn ("I'm in this class because " ++ why)

putStrLn ""

putStrLn ("If you travel for 15mph for 30 hours you will go " ++ show (distance 15 30) ++ " miles.")Try compiling the file with:

$ ghc Hello.hsGHC should produce an executable in the same folder called Hello.

Run it:

$ ./HelloYou should see output. You’ve just compiled your first working Haskell executable!

Now, let’s commit this change.

Use git diff see any changes that we haven’t told Git we want to commit. (Note, this shows changes in tracked files only; Hello.hs is tracked because we already committed it once).

$ git diff

diff --git a/lab0/Hello.hs b/lab0/Hello.hs

index c8f78bd..79cf6e1 100644

--- a/lab0/Hello.hs

+++ b/lab0/Hello.hs

@@ -11,3 +11,13 @@ why = "Want to make computing better."

distance :: Int -> Int -> Int

distance rate time = rate * time

+

+

+main :: IO ()

+main = do

+ putStrLn "Hello, world!"

+ putStrLn ""

+ putStrLn ("My name is " ++ name ++ ".")

+ putStrLn ("I am a " ++ show level ++ " student.")

+ putStrLn ("I'm going into " ++ major ++ ".")

+ putStrLn ("I'm in this class because " ++ why)

+ putStrLn ""

+ putStrLn ("If you travel for 15mph for 30 hours you will go " ++ show (distance 15 30) ++ " miles.")Or, you can see a summary with git status:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: Hello.hs

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

Hello

Hello.hi

Hello.o

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")The Hello executable and a few intermediate files created by Haskell are untracked. Let’s let them be and not commit them.

But we do want to commit our change to Hello.hs. Tell Git to include our change in our next commit:

$ git add Hello.hsNow, actually make the commit:

$ git commit -m "Print out my info"If you run git log, you will now see two commits:

$ git log

commit 32133475e7e83c3ba4017787f4c0d56aab35f058

Author: Brian Hempel <brianhempel@uchicago.edu>

Date: Mon Oct 31 23:01:02 2016 -0500

Print out my info

commit 30a672d7a3b3f615080a7fd79eccaa831f5285dc

Author: Brian Hempel <brianhempel@uchicago.edu>

Date: Mon Oct 31 22:46:35 2016 -0500

Hello.hs with some personal infoThe “Print out my info” commit is still only on your computer.

$ git pushThere you go! Push early and push often.

Each week, when you think your submission is final, you should verify that your changes were pushed:

- Run

git statusto make sure you don’t have any local changes. - Then navigate to the “Files” tab on Gitlab. Make sure you are on the

masterbranch and make sure that your files look right.

If everything looks good, your submission is done. An automated script will grab your repository at the deadline.

There’s one more thing you should know.

Your instructor or the graders may distribute grades by making changes to your remote repository. When there are more commits on the remote repository than on your local repository, Git will not let you push.

You have to first run:

$ git pullThis will pull any commits from the remote repository and automatically merge them with your local changes.

A vim session may open with a commit message saying “Merge … into master”. Save the message and exit vim by hitting :x (colon x).

Afterwards you can run:

$ git pushYou now know everything you need to get started! If your Hello.hs file looks right on Gitlab, you’ve completed this week’s submission.

Below is a bit more miscellanea about Git.

Graphical Tools

For the git add and git commit part of the workflow, a GUI tool may help (I, Brian, use the Mac-only GitX). A GUI helps visualize changes much better. There are equivalent tools for other operating systems. Git comes with gitk, which you might try.

Documentation

There are man pages documenting the different git commands, e.g.:

$ man git-add

$ man git-diff

$ man git-commit

$ man git-pull

...Or:

$ git help add

$ git help diff

...These docs describe an interactive mode for git add that you might find useful:

$ git add -i

*** Commands ***

1: status 2: update 3: revert 4: add untracked

5: patch 6: diff 7: quit 8: help

What now>Of course, you can also search online for tutorials, for example Learn Git Branching and Try Git. (Though we don’t recommend using branches during this course—you don’t want to accidentally forget to push master and fail your lab!)

More Git

The above commands are all you should need for this class, but in the future you may want to learn more about what you can do with Git.

Git gives you complete flexibility. You can grab old versions of files. You can undo entire commits. You can work on different branches to separate different features while you are working on them. You can reorder commits. You can go back in time and change history. (However, a rule of thumb is that you should not rewrite history after pushing.)

For what it’s worth, these are the commands I (Brian) use in my programming workflow. More advanced users may find these interesting. For this course, multiple branches or rewriting history is not recommended.

git add --patch # Okay, really through GitX; but `git add -p` is close.

git rm # Un-stage a change so it's not committed

git commit # Again, through GitX

git commit --amend # Change last commit; (GitX again)

git rebase --interactive HEAD^^^^^^ # Clean up history before pushing!

git commit -a -m "wip" # WIP commits are better than stashing. Never stash.

git reset HEAD^ # Un-commit a WIP commit (but keep changes).

git checkout file_name # Discard changes to file

git checkout -b branch_name # New branch

git branch -d branch_name # Delete a branch

git pull --rebase # Pull, then re-apply local commits

git rebase branch_name # Replay commits on top of branch

git cherry-pick # Apply a single commit from a different branch

git reflog # Recover deleted branches or mistaken hard resetsA Final Recommendation

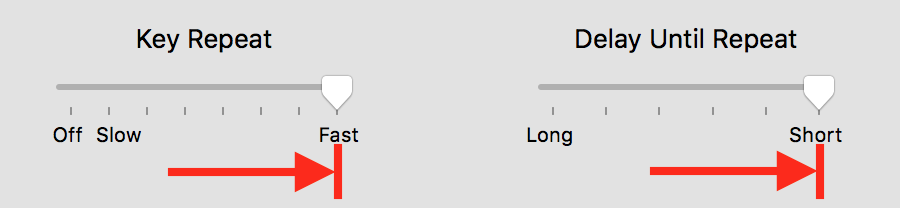

If you haven’t already maximized your key-repeat rate yet in your keyboard settings, you’ll thank yourself later for doing it now.

You’ll quickly get used to it and it will save you days worth of time.

Happy coding!

When you’re comfortable with your setup and you’ve submitted your Hello.hs file, you’re free to leave. See you next week!